You have a decision. You want to choose something good. But what will you call the option you don’t choose?

There are two ways of viewing this choice. Both are helpful, in the right place. I think one has come to dominate our thinking, unhelpfully. What I call good-bad thinking has taken over. I want to keep it, but also hold on to good-better thinking.

Good-bad thinking is just as the words suggest. We choose what is good, and what we reject is bad. I choose to drive at the speed limit (good!) – and choose not to fly through the red light (that would be bad).

Politics and election advertising communicates is always good-bad. Choose Party A, we’re good. Reject Party Z, they’re bad.

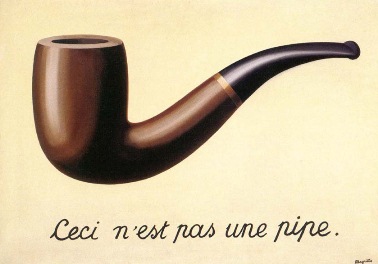

Unfortunately, the good-bad division has become a reflex way to think. It’s automatic. It’s so deeply-held that, when we say one thing, our listeners hear two things.

We say, ‘Evolution fails to explain all reality’ and people hear, ‘We reject science.’

We say, ‘Same-sex relationships are not marriage’ and people hear, ‘I hate gay people.’

We say, ‘Evangelism is of utmost importance’ and people hear, ‘Don’t bother caring for the poor.’

We say, ‘Don’t legalise euthanasia’ and people hear, ‘We don’t care about suffering.’

We did not say that second thing, yet it becomes the centre of the discussion argument.

Good-better

Some decisions – perhaps even the most important decisions – are good-better decisions. There might be two options, both of which have appeal. There might be a large distinction between choices, or the merest hint of a difference – and yet a decision has to be made.

Good-better thinking admits that life can be messy. The non-preferred option might simply be a lower priority, or less clear, or slightly more difficult. A single man might have a couple of ‘just friends’ he could ask to the end of year formal – and feels bad because he does not want to offend one. Because of the expense, a church has to decide between new PA system or new heating. A family has to consider moving away from family for a job, or staying close with uncertain work prospects.

There are plenty of times in life when decisions are both messy and unavoidable.

At such times, it hurts people if we slip back into good-bad. All that does is stick the knife into someone who is already sore! ‘If you move away you’re abandoning family.’ ‘If you put the PA system in you’re ignoring the old folk who feel the cold.’ ‘You asked Grace to the formal because who haven’t forgiven Pearl making that joke about you.’

So what?

My advice – my advice to myself – is to listen better. Do a James 1:19. Be quick to listen, be intent on truly hearing what is actually said. Do not rush into implications, therefores and hasty conclusions. Keep a lid on the righteous (!) anger but hasten to understand. That surely is the better thing to do.

I read

I read