It’s intriguing that (at least) three Bible words have dictionary definitions that include word and thing.

That is, when found in the native environment (in a sentence, not in a dictionary – the zoo for words), it’s possible that each of them could refer to speech, or to an object. For example, in Luke 2:15 the shepherd go to see ‘this thing’ (τὸ ῥῆμα τοῦτο) that has happened: the birth of Jesus. In Luke 2:19, seeing Jesus, the tell others about ‘the saying’ (τοῦ ῥήματος) that was spoken to them.

It’s odd to me, because I am used to dividing between words and things. My words are not reality, and things do not become so simply because I say so. A human promise is good, but not always trustworthy.

That’s where God is so different. When God speaks, it happens. He rules by his word. Likewise, ‘the thing’ exists because God announced it. God’s words are reality.

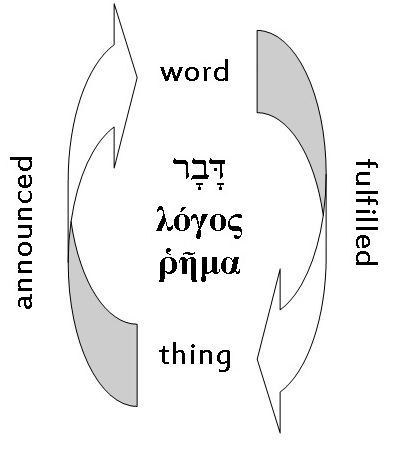

So I tried to put together a visual to help me. Here it is.

You can see the three Bible words in the middle, one Hebrew and two Greek. Above and below are the two concepts that they link: word and thing. The arrows on the sides try to express how word and thing relate (theologically rather than linguistically).

On the right: the word spoken is fulfilled, and thus becomes a thing. God’s word become reality. Perhaps that thing is a physical object: Genesis 1’s ‘Let there be … and there was …’ Perhaps the thing is a state of affairs: ‘I have set my King on Zion’, or ‘You will be my people and I will be your God.’

On the left, the thing only exists because it was announced in God’s word. Creation is contingent, not self-existing. Creation depends entirely on God’s word. Christ upholds everything ‘by the word of his power’ (Hebrews 1:3).

This helps me to see the link. Even more, it helps me to give thanks to God – his word is true, trustworthy and real. What great confidence we can have in the words of our Father!