While at theological college I learned heaps. Mostly this was gradual and grain by grain. There were few ‘light bulb’ moments when a whole new thought clicked into place.

But I remember one light bulb experience.

It concerns generalisations. A fellow student, disgruntled for some trivial matter, shared his general view. “The trouble with all the rectors of Sydney is …”

What an insight this was for me – that a young student believed he had enough knowledge to generalise about well over 200 senior ministers. He knew! My flash of learning: what a stupid thing.

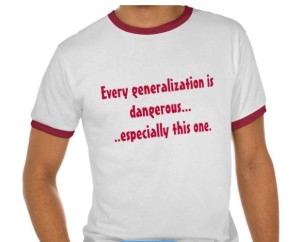

It’s not that generalisations are a problem. It’s that some generalisations are a problem. There are sensible generalisations and there are stupid generalisations. That day I decided I could not trust this student’s generalisations. But I immediately thought of a number of friends whose generalisations I trust.

![]()

I hear people make all sorts of general comments. They can be about men, women, single people, child-raising, churches, atheists, journalists, sports people, musicians, … I try to be careful, even wary. I want to know why do you say that?, how did you reach your that conclusion?

I hear people make all sorts of general comments. They can be about men, women, single people, child-raising, churches, atheists, journalists, sports people, musicians, … I try to be careful, even wary. I want to know why do you say that?, how did you reach your that conclusion?

Many relationship issues arrive packaged as a generalisation. ‘My kids never listen.’ ‘My Bible study leader has a grudge against me.’ ‘My boss hates women.’ ‘My wife has no interest in sex.’

Church conflict shares the same packaging. ‘This church is not friendly.’ ‘No one trusts the pastor.’ ‘All the men are lazy.’ ‘The music team isn’t trying.’

What to do?

I suggest the best way to avoid stupid generalisations is to delay making sweeping statements. Before drawing wide-ranging conclusions, stay with the messy specific details. Listen first, speak later, and really delay anger (yes, it’s James 1:19).

Take the above example: ‘My kids never listen.’ That’s the generalisation – it’s one that can hurt both parent and child. The parent treats it as a universal truth, and might give up trying. The child will pick up what’s going on and likely conform to the expectation.

It’s usually more helpful to deal with specifics. Asking, ‘Why do you say that?’ might lead to: his room is still messy though I told him to clean up; during dinner I asked her about school but she didn’t really acknowledge me; it’s a busy month, so I need to make most of our time together, but it’s not working. Listen to the person, listen to the situation, listen to the details. There might then be a specific way to change.

Just this year I stumbled over the same idea expressed slightly differently. In The Fifth Discipline, Peter Senge warns against the ‘leap to abstraction’. With concrete evidence of short, impersonal staff meetings we might abstract a conclusion that the manager dislikes people. What we did not know is that she has a hearing problem made worse in group settings. Senge says to beware the leap to abstraction. Deal with the concrete as much as possible. Good advice.